By Ofer Aderet May 25, 2012

A pioneering digitizing project led by American experts will now enable members of the community – numbering just 750 – to glance at their past.

Financial problems in the small Samaritan community in Palestine in the 19th and early 20th centuries forced its members to sell their ancient texts to buyers in Europe and the United States. A pioneering digitizing project, developed by Dr. Jim Ridolfo from the University of Cincinnati, will now enable members of the community - 750 people, who live in Holon and on Mount Gerizim, near Nablus - to see what they have been missing.

Ridolfo is collaborating with a team of researchers from Michigan State University, as well as several other academic institutions.

The 32-year-old American scholar, who is in Israel conducting research at Tel Aviv University and visiting the Samaritan community, explained the vision behind the project, which he says goes beyond the boundaries of academia.

"Our goal is to enable the Samaritan community in Mount Gerizim and Holon to have access to ancient Samaritan manuscripts in libraries, archives and museums abroad," explains Ridolfo, an assistant professor of composition and rhetoric, who is writing a book on the project. "This project differs from similar digitization projects, in that we're primarily interested in tailoring the archival interfaces not just to scholars but also to the Samaritan community."

"The project is bringing great pride to the community," said researcher Benyamim Tsedaka, one of the leading members of the local community and a project adviser. "Our manuscripts won't continue to disintegrate, but will be well preserved and transferred to the Internet. The combination of ancient manuscripts and the Internet means easy access, which is a tremendous contribution to the study of Samaritanism and to the community itself."

The Samaritans consider themselves survivors of the ancient Jewish kingdom of Israel, descendants of the tribes of Menashe, Ephraim and Levi. According to the community's tradition, the split between them and their brethren in the tribe of Judah reached its peak when the Samaritans refused to accept Jerusalem as the site chosen for building the Temple, and instead chose Mount Gerizim as their holy place. They write and pray in ancient Hebrew, and celebrate only Torah-based holidays (not Hanukkah or Purim, for example ) on dates that differ from those observed in the standard Hebrew calendar. The Samaritans' high priest is said to be a descendant of Aaron, the brother of Moses.

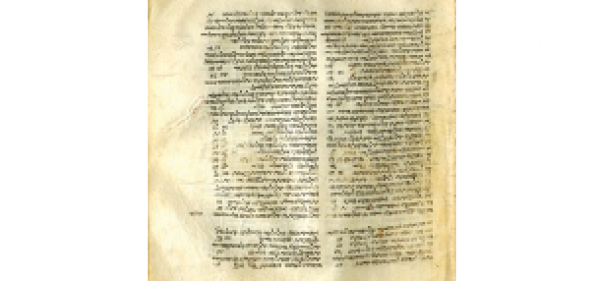

The community's ancient manuscripts are scattered today in museums, libraries and archives all over the world, mainly in the United States, Europe, Australia and Israel. Specifically, members of the community estimate that about 4,000 of them are located in libraries in Manchester, Oxford, Michigan, Paris and St. Petersburg. As part of the current phase of the project, a digital archive of these texts is being established in Michigan as well as at Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati. The codices and scrolls are being scanned and undergoing digitization, in cooperation with the community.

At the end of the project, it is hoped the Samaritans will have all the ancient manuscripts at their disposal in a digital format, on a website, via Facebook and as a cell-phone application. Appropriating the technology of social networks will enable the Samaritans to embark together on the study, translation and preservation of their history.

The community was at its height in the fifth century, when it numbered over a million people. Subsequent changes in governments in the Land of Israel, conversion and various edicts and acts of persecution harmed the community, reducing the number of its members to only 100 by the beginning of the 20th century.

"The financial situation of the Samaritans in Nablus was bad, as a result of the terrible financial distress in the country," said Tsedaka, an elder of the community, who heads the A.B. Institute for Samaritan Studies in Holon and edits its newspaper, The Samaritan News. "The only thing they had were thousands of ancient manuscripts, most of them disintegrating, scattered on stone shelves of the ancient synagogue in Nablus. Hundreds of bound manuscripts remained in private libraries."

Over the years - mainly in the 19th century - books of prayer, Torah, midrash and halakha (Jewish law ) belonging to the community made their way to collectors and scholars of religion. "The Samaritans were in very bad shape financially, which is why they sold their manuscripts cheaply and in large quantities," explains Ridolfo.

By mule and ship

One of the important collectors who purchased Samaritan manuscripts was the Russian Karaite religious scholar Abraham Firkovich. In 1864 he arrived in Nablus and purchased a collection of Samaritan manuscripts that included 1,300 documents comprising more than 18,000 pages.

His assistants loaded the manuscripts into crates, which were transported from Nablus to Jaffa by mule, and from there by ship to the Crimean peninsula. The next stop was the Czarist library in St. Petersburg, which is now the National Library of Russia.

In the early 20th century Edward Warren, a wealthy Christian industrialist and philanthropist from Michigan, came on a trip to Palestine on behalf of a large Christian organization he headed - the World Sunday School. During visits to Jaffa and Jerusalem, he discovered that an ancient community was living in the country, which was being forced to sell its texts in order to survive. After a meeting organized for him with Samaritan high priest Jacob Ben Aaron, he decided to help the community.

"[Warren] was very impressed by the fact that the priest didn't ask for money, but asked for a donation for a school for the Samaritan community, in the hope that it had a future," Tsedaka says.

As a token of their thanks, the Samaritans gave Warren ancient manuscripts of the Torah. "They didn't have anything else to give him in exchange, as a gift for his help. They knew only one form of appreciation - to give away their ancient manuscripts in exchange for bread," Tsedaka explains.

At the same time, the American also purchased additional manuscripts from them, as part of an ambitious plan to store all the manuscripts and when the community was rehabilitated, it would be able to buy them back.

The manuscripts were loaded onto ships and made their way to Michigan. Warren died in 1919 and bequeathed the documents to his children, "who didn't know what to do with the treasure that fell into their hands," according to Tsedaka. First they displayed them in a family museum in Three Oaks, Michigan, but in 1950 they closed the museum and looked for a new home for the works. The collection was gifted to Michigan State College (which later became Michigan State University ). Not knowing what to do with most of the collection, the college stored them in cartons under the bleachers of the football stadium.

During restoration work in the stadium in 1968 the Samaritan manuscripts were rediscovered by Robert Anderson, now professor emeritus of religious studies at MSU, and transferred to a more appropriate facility. Today they are under the care of Dr. Peter Berg, head of Special Collections at MSU Libraries. The most ancient items in the collection are dated from the third to sixth centuries; others, including three Samaritan codices, were written in the 15th century.

For his part, in the 1980s and '90s, Tsedaka was invited to Michigan in order to help document and organize the material.

Meanwhile, in a break-in at the Samaritans' Nablus synagogue in 1995, thieves took two 700-year-old Torah scrolls, which were in daily use. The Israel Police, the Palestinian police and Interpol were mobilized in an effort to find the culprits. But as community spokesman Shahar Yehoshua said last week, "The two scrolls, which are priceless, were never returned to the Samaritans."

Tsedaka returned to Michigan in 2003 and asked the MSU administration to take care of the manuscripts and make them more easily accessible.

In 2007, Jim Ridolfo - who was working in that university's archives then as part of another research project - discovered the manuscripts, entirely by chance.

"I have no special background in biblical or Samaritan studies," he said recently, while in Tel Aviv. "I came to this project from the discipline of writing and rhetoric, and a scholarly interest in the connection between computers and writing studies. I found this project because I was curious about the origins of the Michigan State collection. There's often an interesting story behind the acquisition of these collections," he added.

A short inquiry revealed the entire story, and Ridolfo rushed to send an e-mail to Tsedaka in Holon, proposing that he cooperate in an innovative project that the American researcher had decided to initiate after discovering the texts. Tsedaka agreed and became an adviser to the project in which some 10 researchers are now involved. In addition to Ridolfo, it is headed by MSU's Dr. William Hart-Davidson, an expert on user-centered design. This is an innovative approach that places an emphasis on the users of digitized data - in this case, the Samaritan community - while the project is being planned and designed.

'Wondrous fate'

After receiving initial funding from the U.S. government thanks to a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, part of the material began to be digitally scanned some four years ago; Berg of the Special Collections department, which also provided funds for the scanning, joined in the effort. The next stage was showing the scanned manuscripts to the Samaritans in Holon and Mount Gerizim, to find out how they would like to use the material.

"They told us that digitizing their manuscripts abroad and providing access to their culture is significant to them. We also heard from young people that developing a mobile Facebook application to access the page scans would provide another important level of cultural access to the texts," says Ridolfo, who earlier this month traveled - not for the first time - to Mount Gerizim to observe the Samaritans' traditional Passover sacrifice ritual.

Ridolfo is a guest of Tel Aviv University, as part of the Fulbright International Educational Exchange Program sponsored by the U.S. government, in this case to promote scientific cooperation between Israel and the United States. He is one of 1,200 American scholars who have undertaken research since the mid-1950s under the auspices of the program. In addition to teaching at the University of Cincinnati in Ohio, Ridolfo is also a member of the Digital Humanities organization, which serves researchers interested in digital research, including making ancient manuscripts available to the general public. Additional projects in this field involve works from the Cairo Geniza and the Dead Sea Scrolls.

"The Samaritan archive is a practical example of our ability to translate technology to preserve an ancient and unique culture," Ridolfo says.

To date, parts of the three 500-year-old Samaritan Torah scrolls have been scanned, along with a scroll of the Book of Deuteronomy dating from 1145, which was kept in the archive of Hebrew Union College. At present, access to the digitized material is restricted to the researchers and the Samaritan community. Meanwhile Ridolfo is trying to raise money for continued digitization of manuscripts at MSU and HUC, as well as site and application development.

Although he says there is no connection between the fact that he is Jewish and his involvement in the undertaking, Ridolfo is actually continuing a long tradition of forging connections between the Jewish people and the Samaritans. The most prominent figure in this realm was Yitzhak Ben-Zvi, the second president of Israel (1952-63 ). His first contact with the Samaritans was in 1908, when he was working as a clerk at the Jaffa port and looking for an Arabic teacher.

"One day he came across a store belonging to a Samaritan named Abraham Ben Marhiv Tsedaka Hasfari, who was involved in writing on paper scrolls. The man and his store attracted his attention," says Benyamim Tsedaka (the great grandson of Abraham B. Marchiv Tsedaka). Tsedaka Hasfari invited Ben-Zvi to live in his house, "and there he encountered the great marvel of the Samaritans, and decided to do whatever he could to help them."

Yisrael Tsedaka, the grandson of Tsedaka Hasfari, wrote a few years ago in Haaretz that Ben-Zvi "may have been the first Jew to win the trust of the Samaritans since the paths of Israel and Judea separated."

In his memoirs, Ben-Zvi described the Samaritans thus: "A small sect, the most unfortunate of Jewish sects, which separated thousands of years ago and captured a path for itself. It suffered greatly from the mockery and persecution by its neighbors, the residents of Nablus, but it didn't give up its religion, its language and its customs. And the main thing - it never gave up its homeland and its holy mountain. The Samaritans have not moved from Nablus and from Mount Gerizim to this day ... Wondrous is the fate of the Samaritans. How great is the power of this small and poor tribe that has continued its rebellion against the entire world for thousands of years."